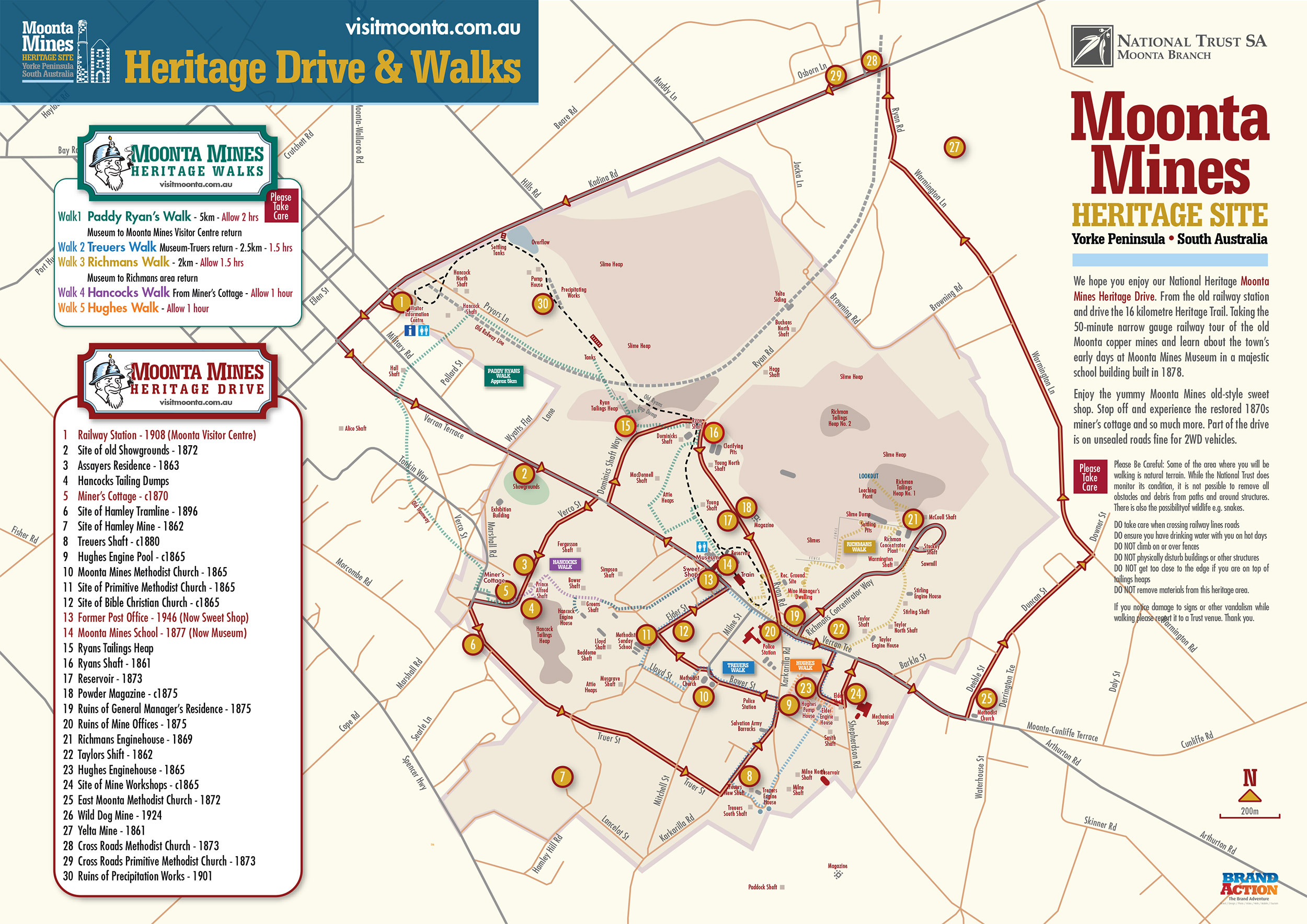

Moonta Mines History

Area History

The town derives its name from a word of the local Narrunga aboriginal people, moonta-monterra, meaning thick impenetrable scrub.

In 1861, a shepherd, Patrick Ryan, discovered traces of copper in earth burrowed out of a wombat hole on the pastoral lease of Walter Watson Hughes. Two parties subsequently applied for mining leases over the discovery, but Hughes was eventually successful. Ryan was paid a reward of £6 per week for discovering the copper, but was dead in 9 months from alcoholic poisoning.

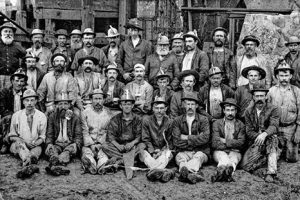

The first miners at Moonta were Comishmen, who used methods developed in Cornwall over several centuries. Cornish miners were recruited from Burra Burra, Kapunda, the Victorian Goldfields and from Cornwall to work in the mines.

Hughes formed the Tipara Mining Association (later the Moonta Mining Co.) and began operations in late 1861, causing a rush of miners from the Burra and Wallaroo mines. The discovery also created a rush for leases in the vicinity and numerous companies were formed, including Karkarilla (later Hamley). Yelta, Paramatta and Poona. However, none of these smaller mines proved as rich or successful as the Moonta Mine.

Early Problems

There was no reticulated water to the area until 1890 when a pipeline from the Beetaloo Reservoir in the lower Flinders Ranges was commissioned. Until then the people relied on rainfall, company built dams and soaks in the sand hills at Nalyappa. This water was sold to the miners. The water collected in the miners’ underground tanks was often polluted by waste from animals and the mines themselves.

Epidemics of typhoid, cholera and diphtheria broke out. In 1873 there were 327 burials in the Moonta Cemetery. There are some 300-400 unmarked graves in the Moonta Cemetery of young children who died during these epidemics.

Mining Methods

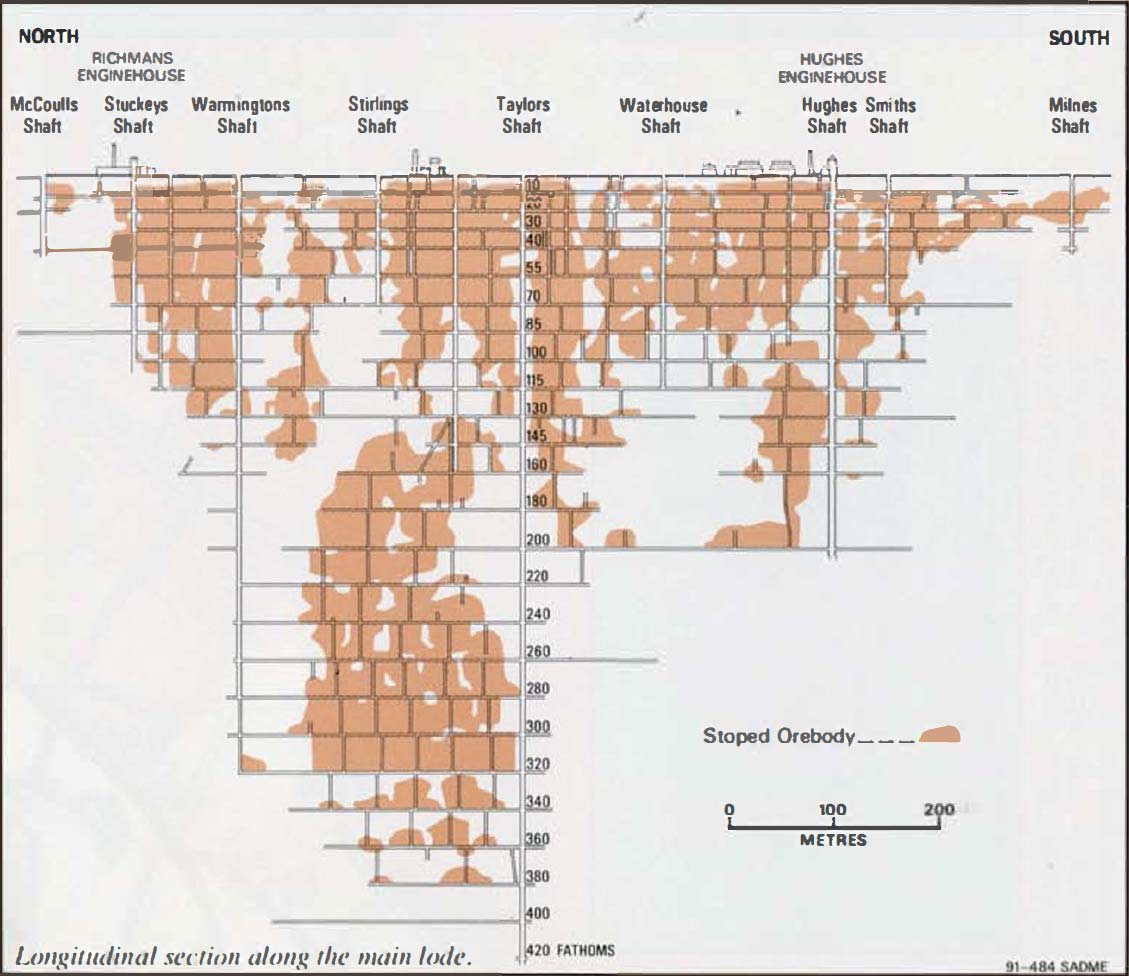

Until the 1890’s all work underground was done by manual labour. No machines were used. The shafts were dug by hand using basic tools and blasting powder. To get from one level to another miners climbed up or down step ladders. Some shafts went as deep as 2,500 feet. The ore was hauled to the surface by horse whims.

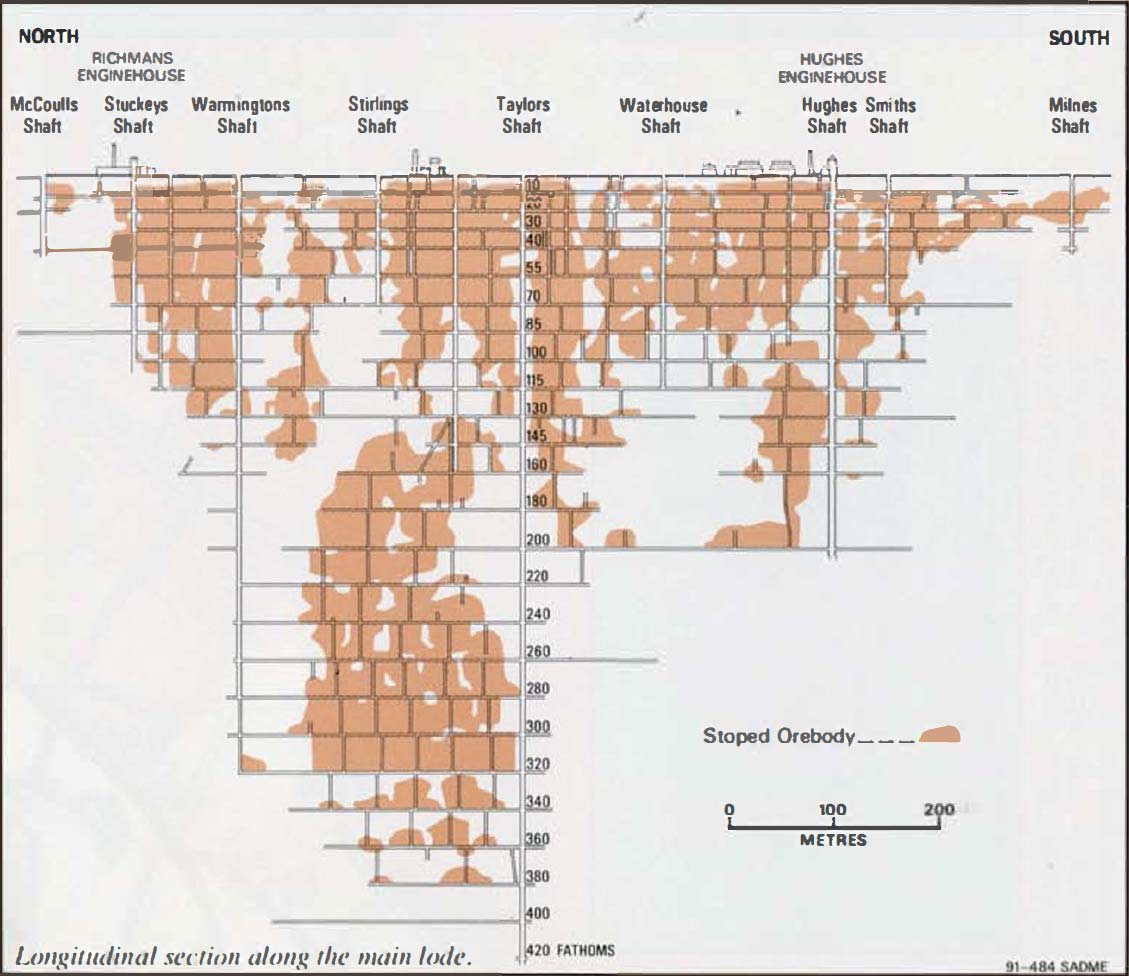

Engine houses were built to pump the brackish mineralized water from the mines. Hughes’ Pump House was constructed in 1865 and worked continuously until the mines closed in 1923. In all there was about 80 miles of shaft and drives in the area.

Engine houses were built to pump the brackish mineralized water from the mines. Hughes’ Pump House was constructed in 1865 and worked continuously until the mines closed in 1923. In all there was about 80 miles of shaft and drives in the area.

The mine was rich from the outset, with nearly 5,000 tons of ore produced in the first year of operation and a dividend of £10 per share was paid on the 3,200 shares. As a result, no further capital was required to finance the mining operations. The mine was managed by Captain James Warmington and later, by his brother William until dismissal of the latter in 1864, when Captain H.R. Hancock was appointed chief captain, a position he held until his retirement in 1898. Under Hancock. the mine developed rapidly and, by 1865, about 1,200 men and boys were employed. By 1870, more than 5,000 people were dependent on the mine, which was producing annually more than 20,000 tons of dressed ore, averaging 20% copper.

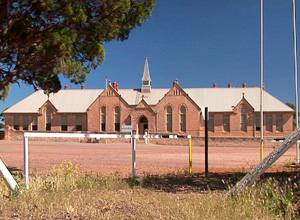

A miner began his working life as a picky boy, whose job was to sit at a table or conveyor belt sorting good ore from waste. After a few years he could join a learn working underground at the rock face sinking shafts and opening drives, this was known as tutwork.

At its peak in the 1870’s around 2,000 men and boys were employed by the Company. Pickey boys were paid 11 pence per day for a 6 day week. 16-21 year olds averaged 3/- to 5/- per day and men over 21 averaged 5/- to 8/- per day. The miners were paid on a percentage of the value of the copper they dug out.

Miners showing promise would then be invited to join a tribute team working the exposed orebody and paid on the amount and value of ore mined. Tributers tendered for an area underground and could make a very good living in rich ore zones. The tribute system was supervised by mine captains appointed by the company. While the lodes were rich, the tribute system worked well, but tribute mining was abolished at Moonta in 1910 owing to falling ore grades.

The early miners, working by candlelight, gouged ore out using a miner’s pick. For many years, blasting was carried out using explosives placed in holes driven by steel bars and sledge hammers until mechanical drills, designed by Captain Hancock, were introduced. Hancock also introduced wire rope and skips. Because of the relatively soft ore, the working shafts at Moonta were usually sunk on the incline down the lode and wheeled skips were used for ore haulage.

At the surface, ore was hand sorted and the high-grade portion sent directly to the smelters at Wallaroo. Lower grade material was crushed and ore separated from the waste or tailings by rapidly moving sieves or jigs. Improvements to the design and operation of these jigs, patented by Captain Hancock contributed greatly to the mine’s profitability by enabling more efficient separation of low-grade ore.

By 1876, Moonta was the first mining company in Australia to pay £1 million in dividends. All that time, employment reached a peak of nearly 1,700 men and boys, but depressed copper prices in the late 1870s brought widespread unemployment. Little development was carried out in the 1880s, when low copper prices resulted in the company’s first losses and the Moonta and Wallaroo mining companies were forced to amalgamate in 1890. The Wallaroo and Moonta Mining and Smelting Co. was the largest mining company in South Australia, under the management of Captain H.R. Hancock and, later his son H. Lipson Hancock.

After 1900 the lodes became unproductive at depth and work was confined to extraction of ore above the 300 fathom (549 metre) level. In 1901 the cementation (leaching) process was established for the extraction of copper from the large tailings (waste) heaps which had accumulated at the three concentration plants.

Five major lodes or ore zones were worked within the mine area. These lodes, which filled fractures within the volcanic country rock, trended north-south and dipped westerly at 40° to 65°. Productive veins initially yielded up to 30% copper but, by 1908, the average grade had dropped to 4%. The principal ore minerals were chalcopyrite and bomite.

After the First World War, activity and prosperity was further curtailed due to a sharp drop in copper prices and limited ore reserves. In 1923, the company went into voluntary liquidation after 2,000 workers at Moonta and Wallaroo refused to accept a drastic cut in wages. The price of copper fell after the First World War and it was costing the Company £14 more per ton to mine it than they were getting at the smelter.

Small-scale mining and prospecting continued until the late 1930s and some high-grade ore remnants were mined at shallow depths. Leaching of tailings dumps continued until 1943. Total production of the Moonta Mine from 1860 to 1923 was 170,000 tons of copper metal valued at £10.7 million.

Social Life

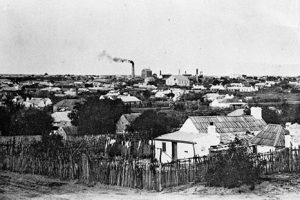

Moonta in the 1870’s was the largest town outside of Adelaide with some 12,000 people living in the area. There were about 80 businesses in the town including 5 hotels and 3 banks. Horse trams operated from East Moonta and Hamley Flat to Moonta Bay from 1869 to 1930.

Methodism was the main religion. Some 16 churches and chapels were built in the area. The Moonta Mines Uniting Church was built in 1865 and is still in regular use. It has the largest seating capacity of any church outside of Adelaide.

Mine Management

The Company was initially known as the Tiparra Mining Company but later changed to the Moonta Mining Company and was financed with a loan of £80,000 from Elder Smith & Co Ltd. This loan was paid back in the first year of operation, and from then on the mine was self financing.

On 4th March 1890 the Wallaroo and Moonta Mining and Smelting Company was formed which all came under the control of Captain Hancock.

Captain Henry Richard Hancock was born in Devon in January 1834 and immigrated to South Australia in 1858. He was appointed Chief Captain and Superintendent of the Moonta Mine in 1864 a position he held until 1898. Upon his retirement his son Lipson took over that role which he held until just before the mines closed in 1923.