The Great Oggie Hunt – Cornish Pasty

One summer’s day just after the Second World War a group of workers at a Cumbrian farm were sitting down to their mid day meal at a table in the orchard. The lady of the house came out and dropped a massive, piping hot meat and potato pie on each plate. No one moved until a Cornishman who worked at another farm nearby, and had been sent over to lend a hand, picked up his pie and eyed it suspiciously. After inspecting it and taking a sniff, he bit into it and immediately spat it out! I’m not surprised you’re not eating them!” he said. They’re awful, the pastry’s all dry and horrible!”

Then, amidst laughter from the Cumbrian lads, the lady came out once more, with her daughters, bearing dishes of vegetables and a huge jug of gravy.

In Cornwall the traditional pasty, or ‘oggie’, is a complete meal in itself and mustn’t, they say, be eaten with anything else. Certainly not with chips and brown sauce, nor with vegetables and gravy. So, with no outside help available except, maybe, a glass of milk, the pasty itself has to be moist and succulent enough to please a Cornishman. No one knows how long the Cornish pasty has been around. But as far back as 1776, it was reported that; “the labourers in general bring up their families with only potatoes and turnips, or leeks and pepper-grass, rolled up in a black barley crust and baked under the ashes, with now and then a little milk. Perhaps they do not taste a bit of flesh-meat in three months”.

The traditional recipe, and indeed the shape, of the Cornish pasty has been modified over the years. A recipe in the October 1890 edition of Cassell’s Family Magazine specified “slices of meat, either pork or beef, mixed with potatoes cut in slices, also swede, turnips and shredded onions. The pasty is the ordinary dripping crust, similar to that used to make large meat pies”.

The old-time Cornish housewife, who frequently just had to make do with whatever was available.

Would make pies and pasties out of anything that walked, swam or flew. It’s said that the devil never dared go to Cornwall because he was afraid they’d put him into a pie!

Early pasties sometimes contained fish, often a whole fish, with the head and tail sticking out of the ends of the pasty (I’m reminded here of Desperate Dan’s famous ‘cow pie!). Sometimes the ‘sweet course’ could be contained within the pasty, too, and there would be fish in one half and apples in the other.

The original Cornish pasty made a convenient package to take food out to the men working in the fields or in the tin-mines.

Fishermen, too, would often take a pasty with them. They could overcome their superstition that nothing land-based should be taken out to sea by knocking the ends off the crust “to let the wind blow through”.

It was from the tin mines of Cornwall that most of the pasty-lore came, however. The pasty has to be able to withstand an accidental drop down the mine shaft but still remain digestible. The tinner’s initial was cut into the pastry before baking so that he could identify his own if he set it aside for a while, and then there was the crimping on the crust! Contrary to popular belief, this goes around the side of the pasty, not over the top (that’s a ‘foreign’ custom – from Devon!)

It’s how a Cornishwoman can tell a genuine pasty at a range of several yards, whereas a Cornishman is said it tell by the aroma.

This elaborate pattern served an important purpose. This was how the pasty was held while eating, for where’s there’s tin, there’s often deadly toxic arsenic. This way no poison could be transferred from the miner’s fingers to his mouth. Naturally, this part of the pasty was discarded.

Tradition demanded that a part of the pasty had to be left, anyway, for the ‘buccas’ of ‘knockers’. These were spirits said to haunt the mines, giving audible warning of an impending rock-fall of other accident, and they wanted feeding in return for their services.

Even today it’s part of the etiquette of the oggie that a knife and fork is never used, although a plate is permissible. I have to confess, though, that I do use them outside Cornwall, because I’m from the North of England, and don’t like brown sauce on my fingers!

The Cornish pasty we enjoy today is fairly standard, and not far away from the 1890 recipe. Beef, of course, and potatoes, onions and swedes. All ingredients should be sliced, never diced or minced – that’s how you tell the inferior ‘supermarket’ version, in which other vegetables are also often substituted.

Although it’s almost traditional to knock the ersatz (imitation) parody of an oggie that has appeared in many places, you can enjoy the traditional taste outside Cornwall.

Although they’ve grown from a small family bakery to one of the largest manufacturers of pasties and snacks in Briton in only 30 years, Ginsters of Callington still keep as closely as possible to the traditional ways of baking their Cornish pasties.

Ginsters told me that their Head Chef, appropriately named Graham Cornish, uses his grandmother’s recipes. His use of chunks of steak instead of mince, fresh local vegetables, and the practice of cooking ingredients together rather than mixing pre-cooked meat and vegetables ensued that, in a recent BBC Radio 4 taste test, his ‘Big G’ pasty was named ‘Best Tasting, traditional Cornish pasty’, beating even many ‘authentic, hand-made ones!

They don’t normally crimp the edges, however. They could if they wanted to, but claim that most customers prefer less pastry and more filling. I can’t argue with it you’ll recall that the crimping was usually thrown away anyway, and most people wash their hands before eating nowadays!

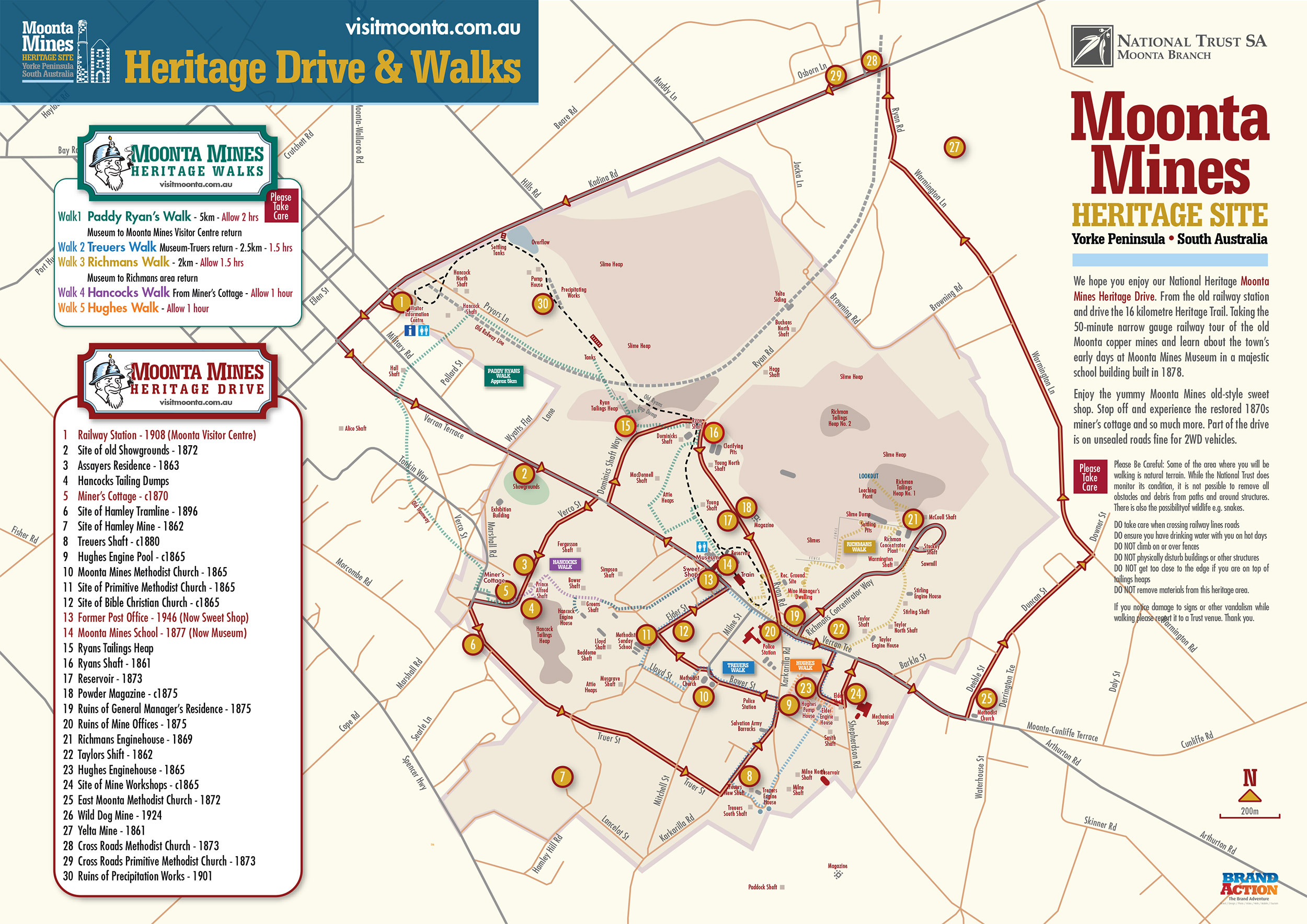

Another of Cornwall’s greatest exports was miners. Mining in Cornwall began in the Bronze Age, so naturally they became rather good at it. If you needed skilled miners, Cornwall was the place to look. Cornishmen migrated all over the world, anywhere where there was mining to be done, and, of course they took their beloved oggies with them.

There are still mining areas in the United States and Australia where the ‘genuine’ Cornish pasty can still be bought. On the Upper Peninsula of Michigan pasties are reported to be available in mining towns such as Iron River or Calumet. I’ve certainly bought mass-produced ones in Australia, although what the old-timers would have thought of my Aussie companion’s habit of inserting the nozzle of a plastic squeeze-bottle into the pasty and squirting tomato sauce into it I daren’t contemplate!

I was preparing to go down to Cornwall to photograph the traditional pasty being baked when, at the Great Dorset Steam Fair, the mountain came to Mohammed! From Penzance came the Cornish Pasty Co. (mobile) Ltd., with a trailer containing a bakery, Cornish bakers and all the ingredients. That was one of the best pasties I ever tasted, and a lot of people at the fair would seem to agree with me. Ask our editor, he saw the queue for them on the Saturday.

(Reproduced with the permission of “Best of British” magazine)